The political situation around rare-earth elements and effects on the auto industry has been a popular topic on social media. Here’s a recent Reddit post by rezwenn:

“Auto companies are 'in full panic' over rare-earths bottleneck”

Hyjynx75 responded with:

“Gosh. If only someone hadn't disrupted international trade relations to the point where China locked down access.”

HarryMudd-LFHL added:

“This is crazy. It's not like China is sitting on the only rare-earth metals in the world. It's just cheaper to use theirs than dig up our own. But then they decide to block exports, and this happens. Maybe we should build some redundancy into our supply chain?”

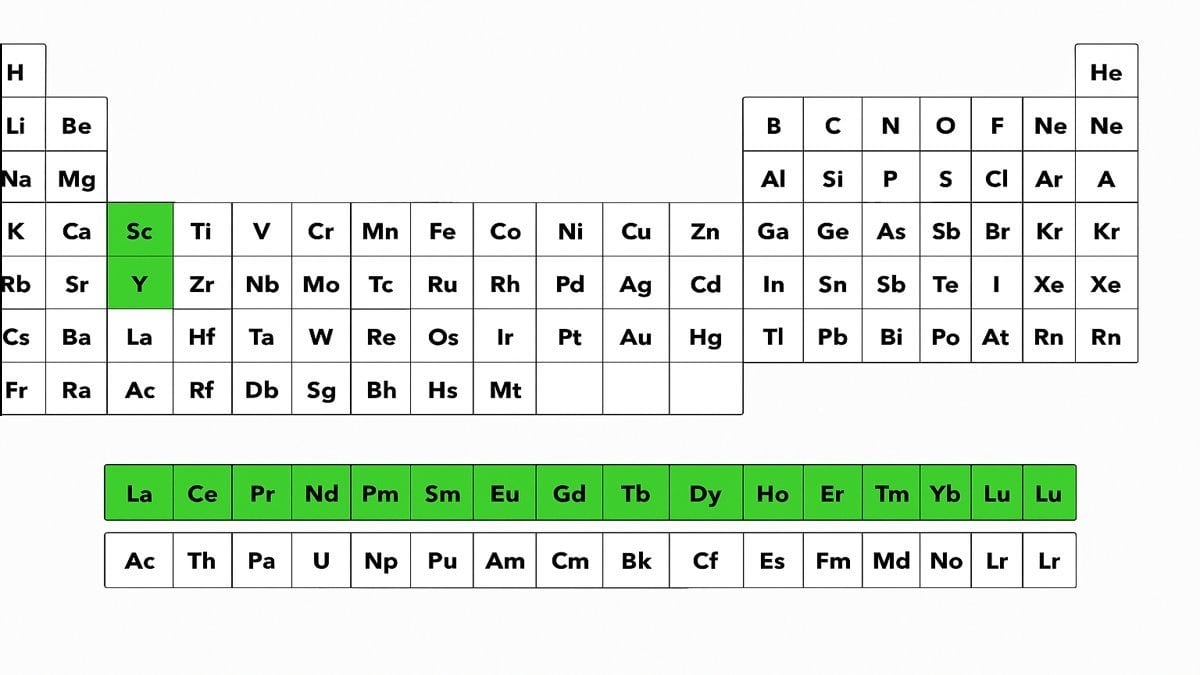

Rare Earth Elements Are Common Elements with Critical Importance

Rare earth elements are not actually rare, so the term often causes confusion. They are called “rare” not because they are scarce in the Earth's crust, but because they are rarely found in concentrated, economically mineable deposits. While rare earths are found all over the world, they often occur in low concentrations and are mixed with other minerals, making extraction and seperation complex and expensive. Their chemical similarity adds another layer of difficulty to the separation process.

Rare earths typically consist of the 17 elements included the lanthanide series (one of the bars at the bottom of the periodic table), as well as scandium (Sc) and yttrium (Y). They are essential to a wide range of technologies, and are used in everything from cell phones and medical devices to wind turbines and weapons systems.

China currently dominates rare earth production, accounting for 60 percent of global mine output and 90 percent of processed materials. In the 1980s, the United States led production and Europe had a major processing facility, but operations shifted due to the high energy, environmental, and health costs of refining. The production process often involves hazardous solvents and generates toxic waste. Some rare earth deposits also contain radioactive elements like uranium and thorium, which has led some countries to avoid mining them altogether due to environmental and safety concerns.

Rare earth elements are often called the vitamins or spice of industry because they make technologies smaller, stronger, and more efficient. Lanthanum (La) and cerium (Ce) are commonly used in lighting and televisions, while samarium (Sm) and holmium (Ho) serve in nuclear power and laser applications. These materials are critical to two especially sensitive areas: military defense and clean energy. They are vital in night vision goggles, precision missiles, and radar, as well as in permanent magnets used in electric vehicle motors and wind turbines. This makes them crucial to global security and climate goals.

How Rare Earth Export Restrictions Are Disrupting the Global Auto Industry

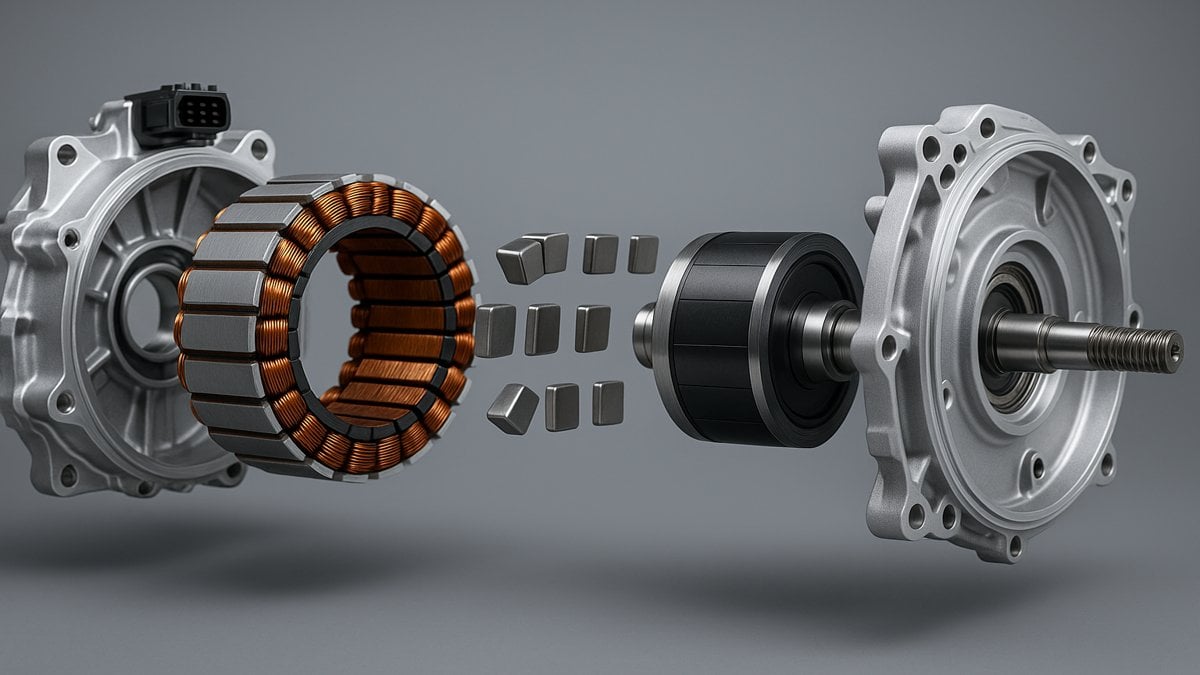

Several traditional and electric vehicle manufacturers are exploring options to move parts of their auto parts production to China in response to the growing threat of factory shutdowns. These concerns stem from China’s restrictions on exporting rare earth magnets to the United States, a result of escalating trade tensions and tariffs. In May, Ford paused production of its Ford Explorer in Chicago due to rare earth shortages, signaling deeper trouble across the automotive industry.

American automakers are scrambling to adapt as rare earth magnet shortages threaten to halt production. These magnets are vital for electric vehicle motors, and even for simpler components like headlights and windshield wipers. Ideas being considered include producing electric motors in China or shipping American-made motors there for magnet installation. This is feasible because Chinese export restrictions target magnets, not complete parts. After the U.S. imposed a 145% tariff on Chinese goods, China retaliated by tightening export rules for seven types of rare earth elements and related magnets, affecting global companies across industries.

Given that China controls 90% of the world’s rare earth supply, the new export controls have disrupted key supply chains used by automakers, semiconductor producers, aerospace firms, and defense contractors. These materials are integral to advanced technologies ranging from smartphones to fighter jets. According to Europe’s auto supply association CLEPA, only about 25% of export license applications are now approved, and approvals are taking two to three months. Electric and hybrid vehicles are disproportionately affected, as they contain more rare earths than traditional gas-powered vehicles.

China has also introduced a magnet tracking system to increase its oversight of rare earth materials. Despite this, China claims the export restrictions are not discriminatory and are open to discussions with other nations. Talks with the European Union have already begun. However, the effects are already visible. Some European production lines have shut down, and more are expected to follow due to dwindling magnet supplies. Automakers are even weighing whether to strip premium features like adjustable seats and high-end speakers to conserve magnets, reverting to older technologies to avoid halting production.

The idea of shipping components globally just to install a tiny magnet shows how desperate the situation has become. Without alternatives, carmakers may eliminate luxuries like electric seat adjustments and superior audio systems. For example, Neodymium, a rare earth magnet, powers high-quality speakers that may be swapped for inferior options. Another approach is to return to older motor technologies that use fewer or no rare earth magnets, though these are generally less efficient and more expensive. Manufacturers are also scouting for alternative magnet sources in Europe and Asia, but current supplies can’t match the industry’s vast demand.

China possesses the world’s largest rare earth reserves at 44 million metric tons, about half of the global supply. Vietnam and Brazil follow with around 21 to 22 million tons. In 2023, China mined about 270,000 metric tons, dwarfing the 45,000 tons mined in the United States. China also dominates the processing stage, refining over 90% of rare earths globally. This is due to decades of investment and expertise in separating rare earths from surrounding rock, an area where Western countries lag behind significantly in both infrastructure and technical proficiency.

The global shift of rare earth processing to China began over 25 years ago under Deng Xiaoping, who famously said that while the Middle East has oil, China has rare earths. With government support and minimal environmental regulation, China undercut Western producers. The U.S. has only one rare earth mine, Mountain Pass in California, which until recently sent most of its output to China for refining. Due to rising tariffs and geopolitical tensions, the U.S. now aims to stop this practice. Yet China remains dominant in both rare earth mining and processing.

Despite international efforts to increase rare earth output, China’s dominance is expected to continue. Rare earths are essential to a wide range of clean energy technologies, including electric vehicles, solar power, and wind energy. This dominance gives China tremendous leverage in trade, military, and geopolitical negotiations. The U.S. depends on China for over 70% of its rare earth imports and more than half of its supply of 19 critical materials. As nations like the U.S., Japan, Australia, and EU attempt to rebuild their supply chains, they face the reality that China has a 20-year head start.

Please Drop Your Thoughts in the Comments Below

Would you give up features like power seats or premium speakers if it meant your new EV could be delivered on time?

Would you support more rare earth mining in the U.S., even if it meant environmental trade-offs?

Chris Johnston is the author of SAE’s comprehensive book on electric vehicles, "The Arrival of The Electric Car." His coverage on Torque News focuses on electric vehicles. Chris has decades of product management experience in telematics, mobile computing, and wireless communications. Chris has a B.S. in electrical engineering from Purdue University and an MBA. He lives in Seattle. When not working, Chris enjoys restoring classic wooden boats, open water swimming, cycling and flying (as a private pilot). You can connect with Chris on LinkedIn and follow his work on X at ChrisJohnstonEV.

Image sources: Caterpillar media kit, AI, AI

Set Torque News as Preferred Source on Google

Comments

Who’s buying the Ford…

Permalink

Who’s buying the Ford Explorer?

The only car worth buying from Ford is the F-150!