For years, electric vehicles have carried a simple promise: even if they cost more up front, they will pay you back every time you skip the gas station.

A recent post in r/TeslaModelX challenges that assumption in a way that feels uncomfortable precisely because the math is not theoretical. It is lived, tracked, and backed up by Tesla’s own app.

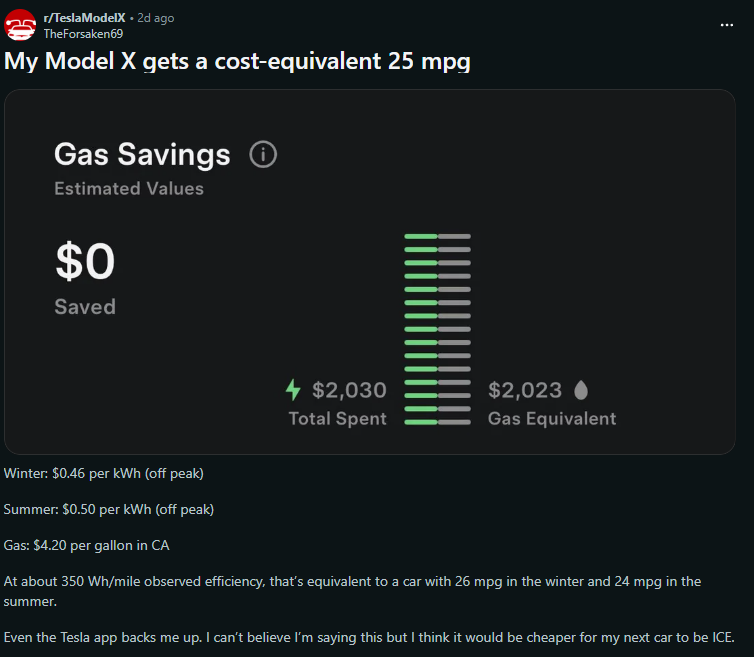

“My Model X gets a cost-equivalent 25 mpg

Winter: $0.46 per kWh (off-peak)

Summer: $0.50 per kWh (off-peak)

Gas: $4.20 per gallon in CA

At about 350 Wh/mile observed efficiency, that’s equivalent to a car with 26 mpg in the winter and 24 mpg in the summer.

Even the Tesla app backs me up. I can’t believe I’m saying this, but I think it would be cheaper for my next car to be ICE.”

The owner lays out the numbers plainly. Winter electricity rates of $0.46 per kWh off-peak. Summer rates of $0.50 per kWh off-peak. Gasoline is at roughly $4.20 per gallon in California. With an observed efficiency of about 350 Wh per mile, the Model X works out to the cost equivalent of roughly 26 mpg in winter and 24 mpg in summer. That is not a typo, and it is not a cherry-picked scenario. According to the Tesla app itself, the driver has spent $2,030 on electricity to cover what would have cost $2,023 in gasoline. Net savings: zero dollars.

Tesla Model X: Falcon Wing Doors & Battery Placement

- The Model X’s tall body and low-mounted battery create a stable feel through corners for a large SUV, though its mass becomes apparent during hard braking and quick direction changes.

- Falcon Wing rear doors improve access in tight parking spaces and ease third-row entry, while adding mechanical complexity and sensitivity to weather and clearance conditions.

- Interior layout prioritizes openness and visibility, with a wide windshield and minimal dashboard controls shaping a cabin that feels airy but heavily dependent on touchscreen interaction.

- Cargo versatility benefits from a flat load floor and front trunk, although third-row use significantly reduces usable rear storage.

What makes this moment jarring is not that electricity can be expensive, but that it has quietly erased one of the core emotional justifications for driving electric. A Model X is not a small car, but neither is it meant to be a fuel-cost wash against an average ICE SUV. When an EV with no oil changes, no exhaust system, and regenerative braking still ends up matching a mid-20s mpg gasoline vehicle on operating cost, the narrative starts to wobble.

The comments quickly zeroed in on geography, and rightly so. One reply summed it up bluntly: this sounds like a California problem. Others refined that diagnosis further, pointing directly at PG&E. In Sacramento, where electricity is provided by a municipal utility, one commenter reported paying around $0.12 per kWh and saving over $1,500 in a year. Plug the same driving into PG&E rates, and the savings vanish. The difference is not driving style or vehicle choice, but the company sending the bill.

Several users highlighted how dramatic the shift has been. Supercharging that once cost $0.05 per kWh in parts of California now approaches $0.50. Residential electricity that sat around $0.16 per kWh less than a decade ago has nearly tripled. That change did not happen in a vacuum, and commenters were quick to note that regulation, wildfire liability, infrastructure costs, and lobbying all play a role. Whatever the causes, the effect is clear. Electricity is no longer cheap by default.

Others pushed back slightly, noting that the original poster’s rates are on the high end even for California. Some reported paying closer to $0.34 off-peak in winter and $0.44 in summer, which still hurts, but does not quite tip the balance in favor of gasoline. Still, the margin is thin enough now that small changes in gas prices or electricity tariffs can flip the equation either way. That alone would have sounded absurd a few years ago.

What is quietly happening here is a reframing of the EV value proposition. The savings are no longer universal. They are conditional. They depend on utility territory, rate plans, access to cheap overnight charging, and whether you rely on public fast chargers. In places like Illinois, where one commenter claimed overnight rates as low as one or two cents per kWh, the old promise still holds spectacularly well. In parts of California, it does not.

This is not an argument against electric vehicles, and the post does not read like one. It is an accounting exercise that happens to land in an inconvenient place. The Model X still offers instant torque, quiet operation, and a very different ownership experience than an ICE SUV. But when the owner admits they are considering an internal combustion car next time purely on cost grounds, it signals something deeper than personal preference.

The uncomfortable truth is that EV economics are no longer guaranteed by the technology itself. They are increasingly dictated by policy, utilities, and infrastructure decisions that owners cannot control. When electricity prices rise faster than gasoline prices fall, the math stops working the way it used to. And when the Tesla app itself confirms that reality, it becomes much harder to dismiss as user error or bad assumptions.

This post is not a declaration that EVs have failed. It is a warning that the transition is uneven, and that for some drivers, in some places, the long-promised fuel savings have quietly evaporated. If electric vehicles are going to remain compelling on cost alone, the solution may have less to do with batteries and motors and far more to do with what shows up on the power bill each month.

Image Sources: Tesla Media Center

Noah Washington is an automotive journalist based in Atlanta, Georgia. He enjoys covering the latest news in the automotive industry and conducting reviews on the latest cars. He has been in the automotive industry since 15 years old and has been featured in prominent automotive news sites. You can reach him on X and LinkedIn for tips and to follow his automotive coverage.

Set Torque News as Preferred Source on Google

Comments

You should be paying road…

Permalink

You should be paying road tax by KWH. Your vehicle causes more damage to the road than my economy car does, yet you do not pay your share of road tax. I pay per mile road tax through gas purchases. You don’t. Sorry if it makes your supposed green car not green anymore. It was just displacing the pollution to another part of earth and raping it of resources that cannot be replaced.

I have PG&E service with…

Permalink

I have PG&E service with EV2 rate of $0.31/kwh. peak can be as high as $0.61. As long as I charge during the off-peak period, I'm ahead.

I think solar panels and a backup battery would be worthwhile, but the payback period is like 8-10 years. I have many mature trees around my home that shade my roof, and the city won't let me cut down those trees for solar panels...

Definitely a CA problem. I…

Permalink

Definitely a CA problem. I have an X. My same chart shows $1500 savings.

it's literally 10 cents when…

Permalink

it's literally 10 cents when you charge at home. Superchargers are meant for traveling. not daily use. morons. and the guy with the Model X is even a bigger moron. bigger income obviously does not equate smarter brain.

$7 a month more for the…

Permalink

$7 a month more for the Tesla that's nothing. we'll start seeing a savings concerning there's a couple of four refiners in California just shut down. Gas prices should jump at least a dollar to a dollar fifty gallon to start. He'll start seeing savings then.

The problem is not the car…

Permalink

The problem is not the car it's California. Even gas prices there are higher then the national average.

Very interesting article…

Permalink

Very interesting article.

What's very concerning is that these charging costs are beginning to expand outside of California. From reports I've seen, the "Supercharger for Business" program that Tesla is setting up with private owners (like Wawa convenience stores, for example) are charging $.39 per kwh. That's not far off the California $.46 rate.

The pg&e rates quoted…

Permalink

The pg&e rates quoted are actually much higher than .40 kwh. In addition to the $/Kwh charge, pg&e also adds multiple other delivery and misc charges. These add up to about .15 to .22 to the base cost of electricity. Also pg&e use a tiered system for pricing. Gasoline is the same cost if you by 10 gallons or 50 gallons Electricity rates jump substantially once you exceed the base amount.

Welp it's the same here in…

Permalink

Welp it's the same here in Maine with electricity rates of 32 cents kwh and gas at 2.70. The breakeven point at 2.5mi/kwh is 21mpg, at 3.5mi/kwh it's 30mpg. CMP(our electric supplier) doesn't offer off peak rates. Home charging is more expensive than driving a gas car. It's been this way the entire time, our state has a 3% EV adoption.

This is true for fast…

Permalink

This is true for fast charging here in MI. Even off peak when it's 36 cents, it doesn't make sense in the winter. However charging slow and at home over night is very cost effective.

Gas includes road tax. My…

Permalink

Gas includes road tax. My buddy got a road tax bill for his Tesla that made him grab his chest....over 5k. He's been trying to sell it for 2 years now w no luck. Battery has degraded 30 percent as well.

The price of gas in…

Permalink

The price of gas in California is about to rise significantly. 30% of refinery capability is leaving the state.

This is an argument for a…

Permalink

This is an argument for a strategy already adopted by France and South Korea, two countries with a large % of nuclear generation that must be curtailed during heat waves, because reactor cooling water gets too hot to release into rivers. The solution? They've both mandated construction of solar canopy microgrids at ALL large (80 spaces) parking lots, nationwide, within 5 years. They're not wasting any time!

Affordable, reliable, widely distributed, solar energy abundance. They're already capturing and storing it, charging EVs, and fortifying local distribution grids right where most residential and small business rate payers live, work and commute from large apartments and condos to shopping centers, business parks and various municipal facilities. No new utility transmission, site acquisition or other site improvement spending required. And no permitting or interconnection delays or armies of litigious NIMBYS.

The only thing flawed with…

Permalink

The only thing flawed with his calculation is premium fuel is not $4.20 in CA in a comparable SUV would likely require it with its forced induction engine.

He also lives in California he should be used to getting screwed over. But I hear the quality life is.. acceptable

My home solar helps make it…

Permalink

My home solar helps make it worth it, but if you have to go to a charging station then it's not worth it at all. Except electric vehicles are so much nicer to drive than ICE so maybe worth the premium to some people, plus not many things to service and no wasted stops at gas stations when charging every night at home.

Sorry that your energy costs…

Permalink

Sorry that your energy costs have exploded. However, you still have no maintenance….factoring oil, and other fluid changes and belts hoses, etc, YOU ARE STILL WINNING.

I’m in the 5th year of driving an EV exclusively and am saving thousands of dollars a year.

PG&E has an EV plan…

Permalink

PG&E has an EV plan which significantly reduces the off peak rates. Also, the rates you're paying looks like supercharger rates which are almost always higher than home charging. If you don't have a home charger then yes, it's expensive and inconvenient to charge

PG&E has an EV plan…

Permalink

PG&E has an EV plan which significantly reduces the off peak rates. Also, the rates you're paying looks like supercharger rates which are almost always higher than home charging. If you don't have a home charger then yes, it's expensive and inconvenient to charge

Just ask Google for oil…

Permalink

Just ask Google for oil company subsidies and pick a year. 2024 for example:

In 2024, U.S. oil companies continued receiving substantial government support through various subsidies, with estimates pointing to tens of billions annually, primarily via tax expenditures like deductions for drilling and favorable treatment of foreign income, despite proposals to cut them; recent analyses show figures like $34.8 billion yearly in federal support, including increased credits for carbon capture and support for oil-friendly tech within acts like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). These subsidies, often hidden in tax codes, are a major form of financial aid, distorting markets and benefiting companies who also spent heavily on political campaigns, securing favorable policies.

Also we aren't in foreign countries for their electricity and technology...

And lastly, show me a 600+ HP SUV that obtains 26mph, or even 20.

and how is the trade in…

Permalink

and how is the trade in value of that ev vs ice?

That is cost at Tesla…

Permalink

That is cost at Tesla charger station

Get a home charger and cut that hugely. Better yet, install solar panels and pay nothing.

Fun fact, about 75% of solar panel costs are paperwork and such. Kick your congressman and get that down!

2 years of experience has…

Permalink

2 years of experience has taught me the same thing. Charging exclusively at high-speed chargers will completely negate the "savings vs gas" positive component of EV ownership (but of course not the others)

But something bugs me about this guy's claimed efficiency. Getting less than 2 mi/kWh seems WAY off especially for something as slippy looking as a model X. Is it the car? His driving style? His numbers? Dunno.

Regardless, with the rates he's experiencing, "solar plus storage" and generating the electricity themselves becomes an even more attractive option (assuming he has a roof to throw the panels on).