John Krafcik is not a man given to hyperbole. As the former CEO of Waymo and one of the literal "godfathers" of the autonomous driving industry, his words carry the weight of decades of engineering rigor. When he speaks, the industry listens—or at least, it should. Recently, Krafcik made headlines by describing Tesla’s Full Self-Driving (FSD) strategy as a "bad case of myopia," a biting critique of Elon Musk’s insistence on a "vision-only" hardware suite.

Krafcik’s argument is grounded in the fundamental physics of perception. Tesla’s current hardware relies on eight 5-megapixel cameras. To Krafcik, this is like trying to navigate a complex, high-speed environment with a data stream that wouldn't even pass a DMV vision test. By dispersing those limited pixels across a 360-degree field, the "effective vision" of the car is equivalent to 20/60 or 20/70 human sight. In layman’s terms: the car is legally nearsighted.

In my years as a technology analyst—and reflecting on my time at IBM where we learned that "good enough" data is the enemy of reliable systems—I’ve seen this pattern before. It’s the triumph of ego over engineering. Tesla is betting that software and "neural nets" can compensate for hardware deficiencies. But as Krafcik points out, no amount of AI can "fix" a camera that is blinded by the sun, obscured by mud, or simply lacks the resolution to differentiate a white trailer from a bright sky.

The Ghost of 2016: When Elon Admitted Vision Wasn’t Enough

It is fascinating how short the public’s memory can be, especially in the tech world. We are currently being told by Tesla that cameras are all we need because "humans drive with eyes." Yet, history tells a different story.

In May 2016, Joshua Brown was killed when his Tesla Model S, operating on Autopilot, drove at full speed into the side of a tractor-trailer that was crossing the highway. The system failed to distinguish the white side of the trailer against a brightly lit sky. In the wake of that tragedy, Elon Musk didn't double down on vision; he actually did the opposite.

During the launch of Autopilot 8.0, Musk explicitly touted radar as the savior of the system. He noted that the new software would use radar as the primary sensor, rather than just a supplement to the cameras. At the time, Musk argued that radar could "see" through objects and environments that vision could not—like fog, dust, or the aforementioned "white-on-white" scenarios. He essentially disparaged the limitations of a vision-primary system, admitting that computer vision was fallible in low-contrast environments.

The pivot back to "Vision Only" years later, removing first radar and then ultrasonic sensors, wasn't a breakthrough in AI capability—it was a cost-cutting measure disguised as a philosophical choice. By stripping these sensors, Tesla saved money, but they also removed the very safety nets Musk once claimed were essential to prevent fatalities.

The Physics of Seeing: Why Occlusion Kills

To understand why Krafcik is so concerned, we have to look at the difference between passive sensing (cameras) and active sensing (Lidar and radar).

- Vision-Only (Passive): Cameras collect reflected light. They are fantastic at reading signs and identifying colors (like traffic lights). However, they struggle immensely with depth perception and "occluded" objects—things that are partially hidden or blend into the background. If a camera can’t see a contrast, the object effectively doesn't exist to the AI.

- Lidar (Active): Lidar (Light Detection and Ranging) fires millions of laser pulses per second to create a high-resolution 3D map of the environment. It doesn't care about the color of the truck or the brightness of the sky. It measures the physical distance to the object with millimeter precision. It "sees" the volume and shape of everything around it, even in total darkness.

- Radar (Active): Radar uses radio waves to detect objects and, crucially, their velocity. It can "see" under the car in front of you to detect the vehicle two spots ahead, providing a "bounce" effect that vision simply cannot replicate.

The primary reason Tesla avoids Lidar is cost. A high-end Lidar unit can cost thousands of dollars, whereas a camera costs less than fifty. But as a former internal auditor at IBM, I can tell you that the "cost" of a system isn't just the Bill of Materials (BOM); it’s the liability and the failure rate. Vision-only systems are far less able to see occluded objects—like a child stepping out from between parked cars or a trailer that matches the horizon.

[Image comparing Lidar point cloud vs camera view in heavy rain]

By relying only on vision, Tesla is essentially asking its software to "guess" the 3D world from a 2D image. It’s an impressive feat of math, but it’s a parlor trick compared to the ground-truth data provided by Lidar.

Waymo vs. Tesla: A Tale of Two Trust Models

When we contrast the approaches of Waymo and Tesla, we aren't just looking at different technologies; we’re looking at different corporate cultures regarding safety.

Waymo, under the early leadership of Krafcik and now Tekedra Mawakana, has taken the "slow and steady" approach. They utilize a massive sensor-fusion suite (Lidar, multiple radars, and high-res cameras) and operate only in geofenced areas where they have mapped the environment to the centimeter. They didn't launch a commercial service until they could prove their cars could operate with no human in the driver's seat.

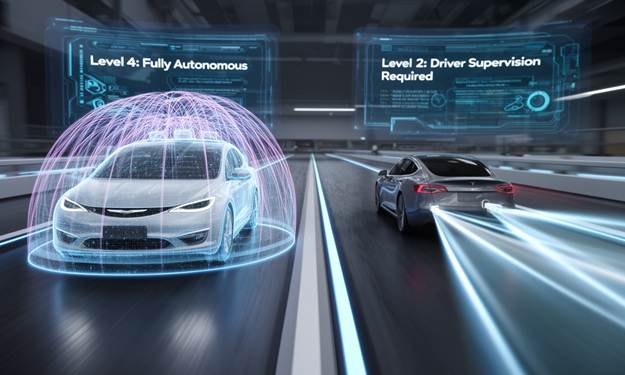

Tesla, conversely, has treated its customers as beta testers. By labeling a Level 2 driver-assist system as "Full Self-Driving," they have created a massive trust gap.

The safety data tells a compelling story. While Tesla recently released new safety metrics claiming FSD is safer than the human average, these numbers are often criticized for lack of transparency and for comparing highway-heavy FSD miles to the general national average (which includes high-risk teen drivers and drunk driving incidents).

Waymo’s data is much more transparent. In cities like San Francisco and Phoenix, Waymo has logged millions of rider-only miles. Recent studies show that Waymo’s autonomous driver is significantly safer than a human in urban environments, with a crashed-involved rate far lower than human-driven counterparts. More importantly, when a Waymo car encounters a situation it doesn't understand, it stops or pulls over. When a Tesla FSD system encounters a situation it doesn't understand, it often disengages with a split-second warning, handing a life-and-death situation back to a likely distracted human driver.

From a perspective of brand trust—something I value deeply as a Jaguar enthusiast and current Volvo XC60 Recharge owner—Waymo feels like an aerospace company, while Tesla feels like a software startup playing "move fast and break things" with two-ton kinetic objects.

The Future of ADAS: When Can You Actually "Sleep" in Your Car?

So, where is this all going? The industry is currently in a state of flux, but the winners are becoming clear.

We are moving toward Level 4 (high automation in specific areas) and Level 5 (full automation everywhere) autonomy. The technologies coming to market now are focused on making Lidar cheaper and more robust. Solid-state Lidar is the next big thing—it has no moving parts, making it more reliable and affordable for consumer vehicles.

We are also seeing the rise of Thermal Imaging sensors, which can detect the heat signature of a pedestrian or animal long before a camera or Lidar can "see" them in the dark.

Timeline for Consumer Ownership:

- Level 3 (Eyes-off, but must be ready to take over): Already here in some markets (Mercedes-Benz Drive Pilot), but very limited.

- Level 4 (Truly driverless in specific zones): We are seeing the first personal Level 4 vehicles, like the Tensor Robocar and Lucid Gravity, targeted for late 2026.

- Level 5 (The Holy Grail): Honestly? We are still a decade or more away from a car that can drive itself through a blizzard on an unmapped dirt road in Montana.

For the average consumer, the ability to buy a car that truly drives itself (Level 4) is likely a 2027-2030 reality. But it won't be a vision-only car. It will be a car that uses a symphony of sensors to ensure that even if one "eye" is blinded, the car still knows exactly where it is.

Wrapping Up

John Krafcik’s "myopia" comment isn't just a jab at a rival; it’s a warning. In the race to dominate the autonomous future, Elon Musk has chosen the path of least resistance and lowest cost. But in doing so, he has ignored the hard-learned lessons of the 2016 trailer crash and the fundamental requirements of safety-critical systems. Waymo has proven that a multi-sensor, "belt-and-suspenders" approach is the only way to achieve true, unsupervised autonomy. As we move toward 2026 and beyond, the market will eventually realize that you cannot solve a physics problem with a software update. If you want a car you can trust with your life, you need a car that can actually see the world in three dimensions, not just one that’s "good at guessing."

Disclosure: Images rendered by Artlist.io

Rob Enderle is a technology analyst at Torque News who covers automotive technology and battery developments. You can learn more about Rob on Wikipedia and follow his articles on Forbes, X, and LinkedIn.

Set Torque News as Preferred Source on Google