For the last decade, the electric vehicle industry has been locked in an arms race that curiously mirrors the Cold War: bigger missiles (batteries) and faster delivery systems (chargers). Yet, despite the hundreds of billions spent on solid-state fantasies and 800-volt architectures, we are still sitting at charging stations for 30 minutes, watching gas-powered cars fill up and leave in five. The industry has been obsessing over chemistry when it should have been looking at plumbing.

A UK-based startup called Hydrohertz has just dropped a technology bombshell that makes the current thermal management systems in your Tesla or Porsche look like Victorian steam piping. It is called the "Dectravalve," and if their data holds up, it doesn't just bridge the gap between EVs and gas cars—it paves over it.

The Thermal Bottleneck

To understand why this is a big deal, you have to understand why your EV charges slowly. It isn't usually because the charger can't deliver the power; it's because your battery can't take it without cooking itself.

Current thermal management systems are surprisingly crude. They generally treat the massive battery pack as a single unit or a few large blocks. When you dump 350kW into a pack, "hotspots" flare up. One group of cells might hit 56°C (133°F) while others are cooler. The moment the hottest sensor hits that red line, the car’s computer throttles the charging speed to prevent lithium plating—a phenomenon that permanently damages cells and can lead to fires.

The result? You might peak at high speeds for a few minutes, but then you plummet to a crawl. You are left waiting, not because the battery is full, but because it is feverish.

Enter the Dectravalve

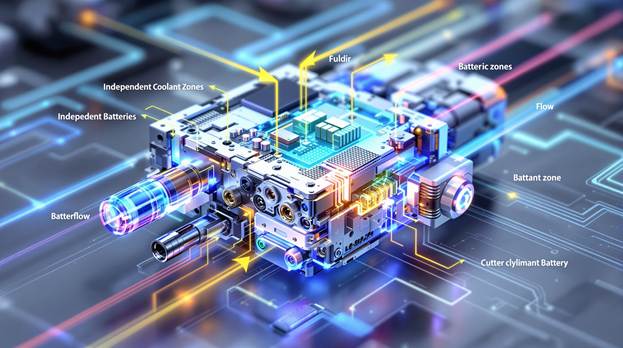

The Hydrohertz Dectravalve is a patented, digitally controlled, multi-zone valve system. Unlike the spaghetti of pumps and valves currently clogging up EV chassis, this is a compact unit that creates independent cooling loops for specific zones of the battery.

Think of it like the difference between a central thermostat that heats your whole house based on the temperature in the hallway, and a smart zoning system that adjusts every room individually. The Dectravalve allows for precise, targeted cooling (or heating) of individual modules.

In testing with the Warwick Manufacturing Group (WMG)—a heavy hitter in automotive research—the results were startling. In a 100kWh Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) battery, the technology kept the temperature variance across the entire pack to just 2.6°C. Compare that to the 12°C spread typical in current EVs. More importantly, it kept the hottest cell under 44.5°C, well below the danger zone where throttling kicks in.

The Magic Number: 10 Minutes

Here is where the rubber meets the road for the consumer. Because the system prevents those thermal hotspots, the battery never has to throttle its intake rate. It stays in the "optimum high-power zone" for the entire session.

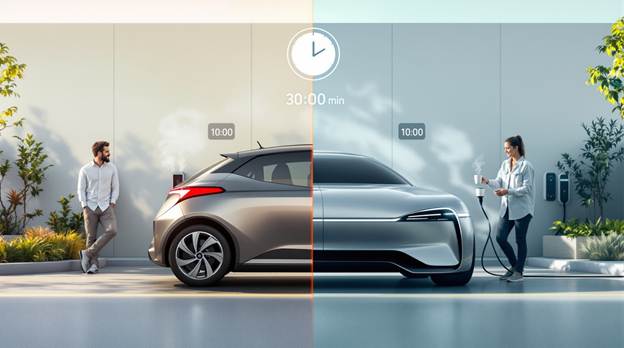

Hydrohertz claims this slashes charging times by up to 68%. We are talking about taking a standard 10-80% charge—which currently eats up about 30 minutes on a fast charger—and knocking it down to 10 minutes.

This is the Holy Grail. Ten minutes is roughly the time it takes to use the restroom and grab a coffee at a gas station. It effectively neutralizes the "refueling anxiety" that keeps millions of buyers clinging to their hybrids and diesels.

Free Range

The benefits aren't limited to the charger. Because the Dectravalve maintains that "Goldilocks" temperature (not too hot, not too cold) while you are driving, the battery operates more efficiently. Hydrohertz data indicates a 10% increase in real-world range.

On a car with a 300-mile range, that is effectively a free 30 miles just from better plumbing. This is significant because it is achieved without adding expensive chemical capacity or weight. It is simply efficiency harvested from waste heat management.

When Will We See It?

This is the multi-billion dollar question. Hydrohertz is a supplier, not an automaker. They have launched the technology now, effectively putting it on the menu for OEMs (Original Equipment Manufacturers).

The good news is that the system is chemistry agnostic. It works with LFP, NMC, and likely even future solid-state batteries. Hydrohertz positions it as a cost-effective upgrade that doesn't require redesigning the entire battery pack.

However, the automotive supply chain moves at a glacial pace. If a major manufacturer like Ford, GM, or a nimble player like Hyundai/Kia bites today, realistic integration into a production vehicle typically takes 24 to 36 months. We might see this in 2027 or 2028 model year vehicles.

That said, the pressure from Chinese manufacturers—who are iterating technology at blinding speeds—might force Western OEMs to fast-track this. If I were a betting man, I would look for this to appear first in a premium platform where performance is paramount, or perhaps from a brand desperate to differentiate itself in a crowded market.

The Advantage Against Gas

For decades, the gas engine's primary defense mechanism has been convenience. You can fill a tank in five minutes and drive 400 miles. EVs have been chasing that metric but failing.

If Dectravalve delivers a reliable 10-minute charge, that defense crumbles. Electricity is already cheaper per mile than gasoline. EVs are already faster and require less maintenance. The only things holding back the floodgates have been upfront cost and convenience.

Hydrohertz is attacking both. By increasing range and lifespan (cooler batteries last longer), they lower the total cost of ownership. By hitting that 10-minute mark, they kill the convenience argument.

Wrapping Up

We often look for the "Jesus Battery"—some magical new chemistry that will solve everything. But history shows that revolutions often come from process improvements, not just raw materials. The steam engine didn't take over the world until we figured out the condenser.

Hydrohertz has realized that the battery isn't the problem; the environment the battery lives in is the problem. By fixing the thermal environment, they may have just unlocked the full potential of the batteries we already have. If this technology scales as promised, the internal combustion engine just ran out of excuses.

Disclosure: Images rendered by Artlist.io

Rob Enderle is a technology analyst at Torque News who covers automotive technology and battery developments. You can learn more about Rob on Wikipedia and follow his articles on Forbes, X, and LinkedIn.