By Eric C. Evarts

Someday, we’ll get out of our coronavirus-imposed isolation, restaurants will reopen, and the world’s roads will again fill with cars. And even after a quiet Earth Day, the price of oil will rebound from being worthless. (Sorry, environmentalists.)

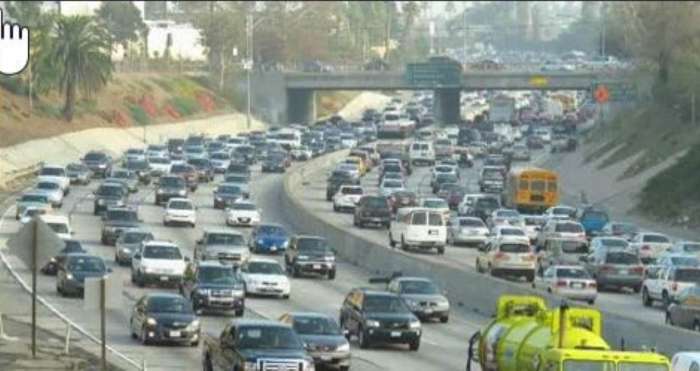

Just as we’ve all gotten used to the clear skies and unclogged roads brought on by social isolation and its attendant lack of travel connections, a new EPA ruling, passed amid the chaotic focus on Covid-19, ensures that Americans will burn a lot more gasoline and create a lot more smog than was expected.

The final version of the so-called Safe Affordable Efficient Vehicles Rule (“SAFER”), was passed March 31, under largely self-imposed April Fool’s Day deadline, rolls back unified fuel-economy increases set by President Obama during the last financial crisis—when the biggest concern was oil prices becoming unattainable, rather than collapsing.

The new rule limits increases fuel economy standards to 1.5 percent per year through 2026, while the original law was set to raise fuel economy standards by 5 percent per year through 2025. Under the old standards cars and trucks were expected to achieve fuel economy levels of about 54.5 mpg by 2025 on paper. The new rules will limit that to just over 40 mpg. Real-world fuel economy numbers will be significantly lower in either scenario.

Under the original rules, cars in many categories have seen their fuel economy improve dramatically with new technology such as 8, 9, and 10-speed transmissions, direct fuel-injection, and a proliferation of hybrids as well as electric cars. The final years of the plan—now rolled back—were to affect primarily larger vehicles such as pickup trucks and large SUVs. Pickups accounted for not quite 17 percent of the market in 2019 but consume an out-sized portion of fuel for every mile they drive, because of their bulky size and hulking weight.

While a draft of the new rules proposed freezing fuel-economy requirements starting next year, the final version passed last month reduces the required increases to a level that most automakers had already baked into their product plans. new rules run more than a thousand pages to justify the planned rollbacks in fuel economy requirements.

Environmentalists noted that when the EPA first proposed to roll back the requirements under the Trump administration, the justification was thin and mostly political, rather than fact-based.

The final rule rolls out more than 2,000 pages of documentation to provide economic justification for why higher standards wouldn’t be worth the cost, both to consumers and the country. Since 1981, federal agencies have been required to publish cost-benefit analyses of virtually every new regulation they pass. It’s included in this new ruling’s Final Regulatory Analysis (PDF).

Few lawyers, politicians, or lobbyists—much less journalists—have time to read and digest 2,000 pages of complex equations wrapped in confounding legal arguments.

Fortunately, our friends at Consumer Reports, one of the nation’s leading consumer advocacy organizations, did. In a policy paper released last week, the organization picked apart the arguments and found them riddled with both illogical conclusions and erroneous arithmetic.

“The agencies' own analysis shows that this rollback is a loser for consumers. If you go in and correct all the questionable choices baked into the analysis it looks even worse. Either way consumers are poised to lose billions at a time when they can least afford it,” says Chris Harto, Senior Energy Policy Analyst at CR.

It’s worth reviewing some of their findings.

- Perhaps most critically, the regulatory impact analysis assumed that batteries for electric cars and plug in hybrids will stay higher than almost any experts are expecting. In 2019, lithium-ion battery packs for electric cars cost $156 per kilowatt hour, the equivalent of about 0.1 gallons of gas, according to BNEF, the new energy analytics wing of Bloomberg. So far, that has made electric cars more expensive than equivalent models that run on gas. Experts have forecast that electric cars will be able to compete head-to-head with gas cars when that cost falls to $100 per kWh, so the rate at which engineers can bring down those costs is key to any analysis of whether requiring more cars that run on electricity more of the time is cost effective.

The EPA and the Transportation Department, which jointly published the new standards, factored in a 4.5 percent annual decrease in battery costs, when in fact, those costs have been steadily decreasing at more than 10 percent per year. Even in its “worst case” (for the agencies’ argument to relax the laws) scenario, the document assumes a 6 percent annual decrease. The discrepancy could add $21 billion to the cost of rolling back the regulations, according to CR’s analysis. - Since all these future analyses are uncertain especially when it comes to technology cost, regulators build in a technology markup fudge factor. Determining such a fudge factor is, of course, an inexact science. Generally accepted practice is to turn to industry experts to develop a range of likelihoods. The EPA considered this method it said in its report, but rejected the idea and instead chose its own multiplier of 1.5 for the costs of installing all technology needed to meet the higher former fuel economy rules. Compared with available forecasts by industry experts, that added 22 percent, or about $23 billion to the comparative cost of the old rules (imputing the same amount to savings under the new rule.)

- Based on sales numbers from years past, the agencies also limited the number of pure electric cars (those with no gas engine) that automakers can sell in their cost-benefit analysis. Sales of the Tesla Model 3, which became the bestselling luxury car in America, belie that assumption. The agencies allow that higher EV sales could bring bigger benefits, but don’t factor that into their financial analysis. If they had, it could have added $13 billion to the benefits of keeping higher standards.

- The financial impact analysis also counted $32 billion in extra gas taxes consumers would pay from increased consumption as a benefit to public tax revenue as well as a cost to consumers. While members of the public may well reap some benefit from that extra tax revenue, it’s not clear it’s a one-for-one calculation and is likely larger than any actual benefit those consumers may benefit from.

- The agencies double counted the so-called “rebound effect”—the tendency for people to drive more and commute farther in cars that get better gas mileage. (Statistically, the effect is well documented, although any causal relationship is less clear-cut.) Recent research has shown the “rebound effect” to be less than 10 percent, yet the agencies factored a 20 percent rebound effect, double what the previous rule counted. Dropping that to 10 percent would add $22 billion to the cost of the rollback.

- The EPA analysis also assumes that less-efficient “light trucks,” SUVs pickups, and wagons—the vehicles most affected by the looser fuel economy rules—will make up 44 to 47 percent of sales over the course of the law (through 2026.) Consumers have been turning to those SUVs in droves, however, and together with trucks they made up 67 percent of the market in 2019. So the increased fuel consumption from the change was undercounted, though by what amount is unclear.

- Since the basic laws of supply and demand dictate that consumers will buy less of a more expensive product, the analysis included lost sales from the higher cost of cars with additional fuel-economy technology as justification for rolling back the requirements. Any lost sales—as well as any increase in sales based on expected long-term fuel savings from more efficient vehicles—are calculated based on an expected rate-of-return on the consumer’s investment in better fuel-economy technology. In the final rule, the EPA quadrupled the estimated effect of increased cost in lost sales compared with the original rule, including the effect of that increase on lost jobs in the auto industry and beyond.

- When it comes to fuel savings, the EPA assumed that only the first 2.5 years of fuel savings matter to new-car buyers, and failed to account for any value from additional years those more fuel-efficient cars would be expected to be on the road.

Together, those last two calculations added at least $16 billion in savings to the new rule, the Consumer Reports analysis showed. - In its original call to roll back the rules, the Trump administration fell back on an old argument that more fuel-efficient cars are smaller and more dangerous. Only in this case, since the technology to make cars more efficient sometimes adds weight, they argued that the higher cost of cars with such technology (estimated at $977 in the report), will cause people to hold on to older cars with fewer safety features longer—resulting in more highway deaths. (Fundamentally, this tradeoff is why the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, not the EPA, officially governs fuel-economy standards. The EPA governs emissions standards, but a 2007 Supreme Court ruling that global-warming-causing carbon dioxide is a pollutant that falls under the EPA’s authority, the two have had to be coordinated.)

To turn that into a cost-benefit analysis requires putting a price on a human life potentially lost in a car crash or as a result of pollution. In its financial impact analysis, however, the administration puts a higher value of $10.4 million on a life lost to a car crash than one lost to pollution: $8.7 million. The total effect isn’t clear because there is some uncertainty around health impacts from pollution, but it clearly values safety higher than health and skews the analysis to favor rolling back the standards. - Beyond that, in some places, CR found the agencies just get the math wrong. In calculations of consumer savings per vehicle, for both cars and trucks, the analysis shows a higher number than the “fleet average,” which is mathematically impossible. You can’t average two numbers and get a result lower than either factor. In perhaps the most critical calculation in the analysis, the savings per vehicle doesn’t seem to add up from the estimated price increase minus the lifetime fuel savings. Again the discrepancy seems to favor lower standards.

All told, the financial analysis says that the rollbacks will cost the country $13 billion. Adding these discrepancies drive that up by another $111 billion—at least Consumer Reports found.

Torque News reached out to the EPA for comment on this story and was referred to NTHSA for answers. However, we did not hear back from NHTSA before publication.

Amid coronavirus shutdowns, concerns about fuel savings and emissions reductions may seem far off. But the lack of travel associated with social distancing has given people around the world a glimpse of the possibilities for a brighter future—not to mention views of the Himalayas and the San Gabriel Mountains in Los Angeles. Burying this proposal to return to old levels of pollution seems a missed opportunity to find a better way forward.

Eric Evarts has been bringing topical insight to readers on energy, the environment, technology, transportation, business, and consumer affairs for 25 years. He has spent most of that time in bustling newsrooms at The Christian Science Monitor and Consumer Reports, but his articles have appeared widely at outlets such as the journal Nature Outlook, Cars.com, US News & World Report, AAA, and TheWirecutter.com and Fortune magazine. He can tell readers how to get the best deal and avoid buying a lemon, whether it’s a used car or a bad mortgage. Along the way, he has driven more than 1,500 new cars of all types, but the most interesting ones are those that promise to reduce national dependence on oil, and those that improve the environment. At least compared to some old jalopy they might replace. Please, follow Evarts on Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn.

Set as google preferred source

![Cars spew exhaust in morning freeway traffic [CREDIT: Lawrence Berkeley Lab] Cars spew exhaust in morning freeway traffic [CREDIT: Lawrence Berkeley Lab]](/sites/default/files/styles/hero_image_small/public/images/traffic_taillights_lawrence_berkeley_lab_sized.jpg?itok=wNQAAW8Z)

Comments

“Few lawyers, politicians, or

Permalink

“Few lawyers, politicians, or lobbyists—much less journalists—have time to read and digest 2,000 pages of complex equations wrapped in confounding legal arguments.” Good observation. Another observation: Nowhere have I seen the desires of consumers mentioned; it seems not to be grasped that We The People (consumers) are paying all the bills but have no meaningful input in the matter of fuel economy and most issues automotive. This is not how a free-market capitalist system operates. The auto manufactures will be paying the price for the illegitimate, bureaucratic morass, that is the present.

Thank you for this article

Permalink

Thank you for this article Eric. Unfortunately, it reminds us that the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) which was established in December 1970 with the expressed mission to protect human and environmental health, is currently a slave to the big oil companies, who have grown rich and powerful over the last century extending the dominance of the petroleum industry, at the cost of human and environmental health. Kudos to Consumer Reports to show the obvious foundation of lies in the EPA's roll back decision.